Research

One major emphasis is binding prediction

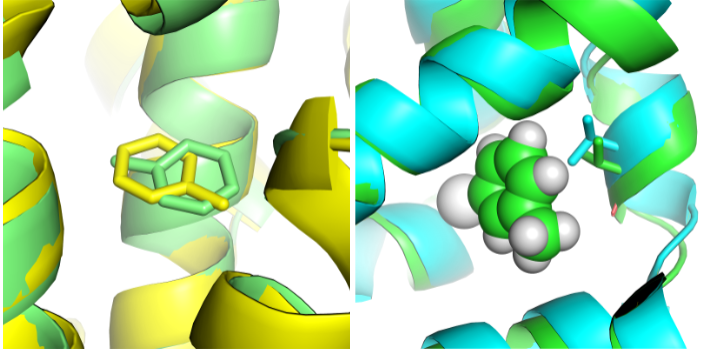

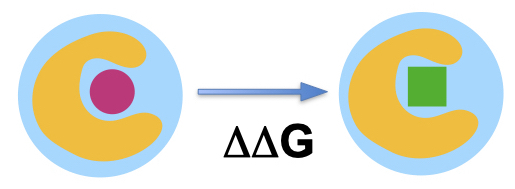

A major focus is the binding of small-molecule ligands to proteins. While current computational methods see widespread use in the pharmaceutical industry in drug discovery applications, accuracy is limited and these approaches fall far short of the goal of using computers to suggest new drug candidates. Methods we recently developed and applied have achieved far greater accuracies at computing and even predicting binding affinities than previous methods, so we are working to begin applying these in more complicated and pharmaceutically relevant binding sites. Projects involve both applications to drug discovery problems, and methodological improvements. Our work in this area focuses on using so-called alchemical free energy techniques for predicting binding affinities using molecular simulations. (See alchemistry.org for more.)

Alchemical free energy calculations turn off interactions between the protein and the ligand in a set of simulations, allowing transfer of the ligand from the binding site to solution and yielding binding free energies.

We continue to advance methods for binding prediction using model binding sites:

Previously, we pioneered techniques for computing absolute binding free energies, applying these first in several model binding sites — an apolar binding site in T4 lysozyme, and then in more polar version of the binding site which introduces hydrogen bonding, and finally on a charged binding site in Cytochrome C peroxidase. This included work on handling uncertainty in ligand binding modes. Follow-up work dealt with how protein conformational changes adversely affect relative free energy calculations. We continue to work in the space of model binding sites occasionally, including recent work on how crystallization conditions like temperature impact structures and binding calculations.

One major avenue of current research involves the separated topologies method for binding free energy calculations, which we introduced in a proof-of-principle study in 2013 but only began to push forward recently. In a collaboration with Pfizer, we’re working to turn this into a production-level method which can be broadly used for flexible free energy calculations in industry, and preliminary results look promising.

We apply binding free energy techniques

We seek to design around minor changes in an enzyme active site to develop new antibacterials.

We have several more application-oriented problems of binding free energy techniques. For example, we are collaborating with Jeff Perry’s lab at City of Hope on several cancer targets and in other therapeutic areas. We’re also collaborating with Marcus Fischer (St. Jude) in several areas including HSP90 inhibitor discovery, and we’re involved in a budding neurotherapeutics institute at UCI.

Hydration free energy calculations and solubilities

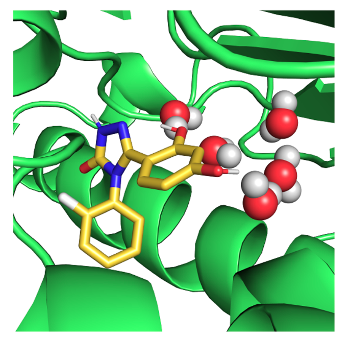

Hydration free energies are important for several reasons. One is simply that it is now possible to calculate these extremely precisely for small molecules, enabling quantitative comparison between simulations and experiment. They are also thought to provide some idea of the level of accuracy that can be expected in drug discovery applications. Finally, they provide a probe of the underlying physics of hydration. These reasons make them rather interesting for computational studies.

Previous work on hydration free energies

We have a long history looking at hydration free energy calculations using alchemical free energy techniques, beginning with testing a variety of different charge models and two water models for hydration free energies of around 40 different molecules (see also follow-up). Later, we did blind predictions of hydration free energies on several different occasions, most recently just a few months ago. We also looked at solvation of more than 500 different molecules in both explicit and implicit solvent, providing what is becoming a standard dataset for hydration free energies which we have expanded into the FreeSolv database (which we just updated and revised). We have also highlighted how water asymmetrically solvates solutes of opposite polarity. However, new experimental hydration free energies are becoming a rarity, so we are moving in the direction of other, related properties as tests and benchmarks for forcefields (and fodder for the SAMPL series of blind challenges), including relative solubility, partition coefficients, and distribution coefficients (see also the SAMPL6 distribution coefficient challenge we coordinated).

Ongoing projects

Ongoing work in this area mostly focuses on the SAMPL series of blind challenges, which have moved in the direction of logD and logP prediction for transfer between phases, though we have also worked on calculation of infinite dilution activity coefficients. With the SAMPL challenges, we arrange for data collection (or release) of new experimental results so the community can engage in blind predictions prior to release of the data, allowing methods to compete head to head and crowdsourcing new innovations. This has been instrumental in driving progress in the field, from solvation modeling to binding prediction.

The Open Force Field Initiative

We’re very excited be part of building better force fields for molecular simulations, and building a better way to make new force fields. We helped found the Open Force Field Initiative, a large academic and industry collaboration designed to advance science, software, and force field quality in this area. Much of the new science of our work is funded by the National Institutes of Health, and a large consortium funded by the pharmaceutical industry helps support our software and product development efforts. This work has already produced the most accurate public/open general small molecule force field, and much more is in progress and planned.

Methodology, Sampling Techniques, and Tools

Previously, we highlighted the importance of soft core techniques for binding free energy calculations, and the importance of long-range Lennard-Jones interactions in obtaining free energy estimates that are robust with respect to the choice of LJ cutoff. We have also developed a framework for including free energies of slow protein conformational changes in binding free energy calculations. More recently, we collaborated on enhanced sampling techniques for improved conformational sampling of small molecules using expanded ensemble techniques. We also worked extensively on enhanced sampling of ligand and protein motions via our BLUES package, which includes methods for better sidechain sampling in torsions and rotational degrees of freedom. We continue to be interested in general strategies for better sampling of slow degrees of freedom in free energy calculations, and as noted above, are focusing on the separated topologies method for relative free energy calculations as well.

We make free energy calculations easier to apply:

A major bottleneck in using these calculations in a drug discovery setting has been the difficulty of setting them up, and the expertise required to do so. We are working on new tools to make free energy calculations dramatically easier to apply, including a tool for automated planning of relative free energy calculations, Lead Optimization Mapper (LOMAP, GitHub). We also helped launch the Open Free Energy Initiative recently, and are partnering with them on ongoing work in this space.

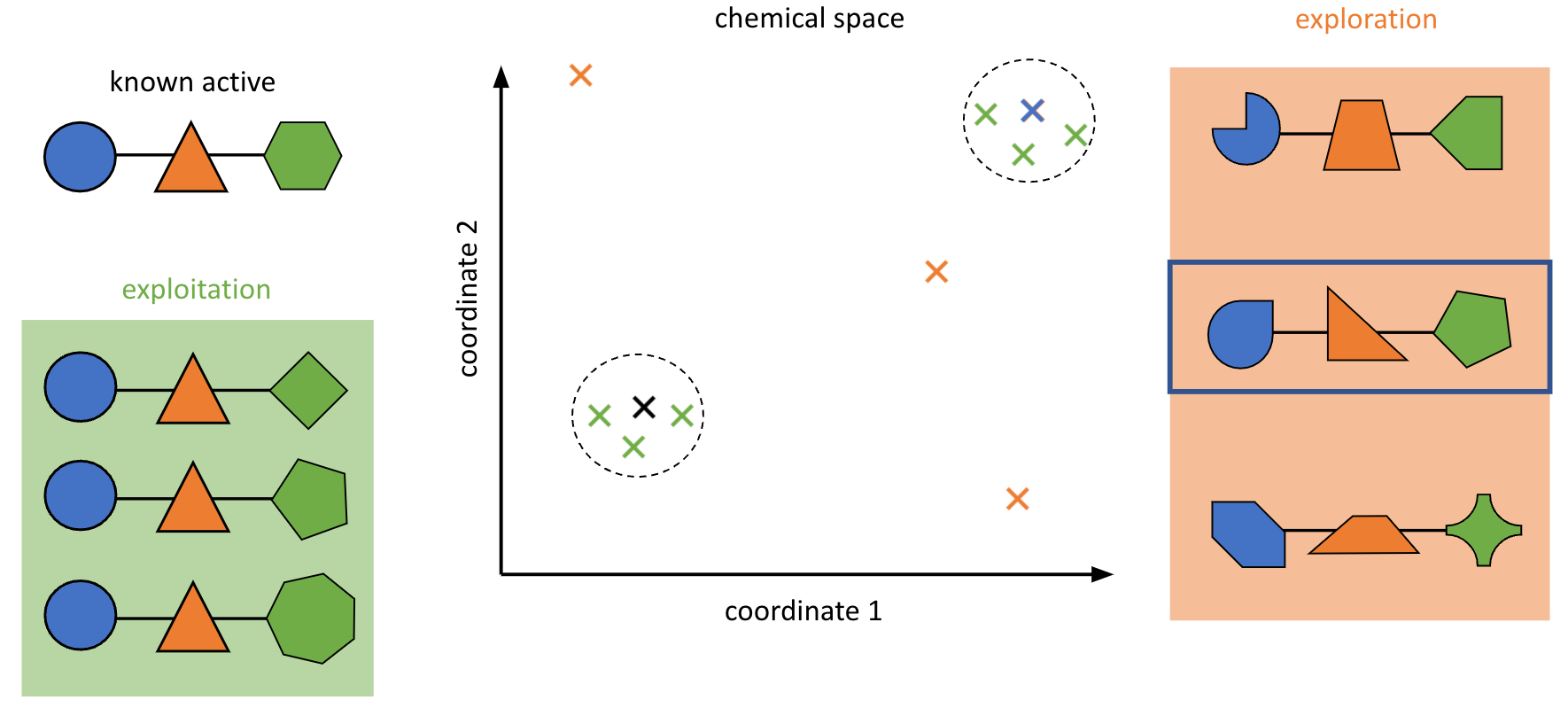

We’re improving free energy calculations via compound screening

Building on LOMAP, we’re also investing effort in more optimal planning of free energy calculations to guide compound screening. New results from the lab provide insight into how to improve the accuracy of predictions via better calculation planning and prioritization, and how errors can be dramatically reduced by including key additional calculations in compound prioritization. This work will also couple with our separated topologies approach, allowing traditional and separated topologies to be used together to efficiently explore multiple compound series, including when planning scaffold hopping.

We’re interested in library design and compound screening:

We’re also partnering with the Paegel lab at UC Irvine in several different areas, including library design and compound screening. In particular, the Paegel lab’s unique technology for combinatorial screening via DNA encoded libraries provides a number of exciting opportunities to interface with computation. We’re working on designing screening libraries that are maximally informative and combine building blocks in ways which more efficiently explore chemical space than traditionally designed libraries, and we have plans to extend this to design libraries more suited to antibacterial and antiviral discovery. We’re also working on techniques to learn from the results of DEL screens and improve the quality of our models and subsequent screens. DELs have the potential to generate vast amounts of data, making them interesting for machine learning (ML) methods, whereas at lower data quantities physical methods are more appealing; exploring this tradeoff will be interesting.